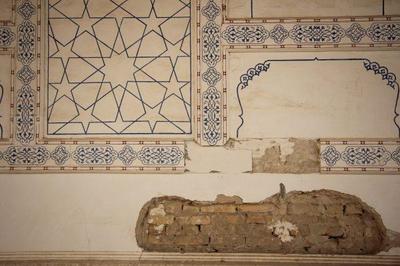

Dushanbe demolishes iconic Rohat Teahouse

The iconic teahouse, known as Choihonai Rohat in Tajik, is the latest victim of the city-wide redevelopment boom in Tajikistan’s capital, although it seemed for years that the building would be spared. Over the past decade, locals have watched Dushanbe transform from a Soviet-built town known for its quiet tree-lined avenues into a dusty, bustling city full of glass highrises and grand administrative buildings. In the process, much of the city’s Soviet heritage has been erased, as Tajikistan reimagines what it means to be an independent Central Asian republic with its own national identity.

Filters & Sorting

Filters & Sorting